We love reading about the history of food, particularly about haggis. Every culture on this earth has a way to cook the innards of animals killed for their meat. Meat is much easier to store, carry and to cure than the 'pluck' (or offal) - all that yummy stuff that comes out of the body cavity like the heart, lungs, liver and kidneys. And then of, course there is the blood, another valued ingredient, but is not used in making haggis.

Early Nose-to-Tail Preservation

So, imagine you are a Paleolithic guy who has successfully downed a large mammal and are ready to eat it. It's easy enough to poke a stick through a leg or haunch and roast it over the fire.

But what do you do with the bits from inside that won't stay on a stick and are either too small or too fragile and fall into the fire never to be enjoyed. You need something to hold them above the flames, some kind of skin or pouch!

Who knows how much trial and error was involved before some smart caveman figured out you could use the stomach as a cooking vessel - stuff your choice innards inside, tie up the open ends and hang it from a tripod of three sticks above the flames. Long before cast iron pans and Tupperware containers, stomachs were used as cooking vessels and containers for carrying foods to be eaten later.

Cooking the offal soon after death is important as these tender organs deteriorate quickly, so finding ways to preserve them for future consumption was another challenge. Bound inside the stomach or bladder, then cooked, they actually became easier to transport and eat later.

How long ago, you ask? In Aristophanes' "The Clouds," there is a passage about preparing a feast in a sheep's bladder. Socrates' friend, Strepsiades, gives an account of being served a "stuffed paunch," which was not given a "vent" before cooking and burst, covering him with "its rich contents of such varied sorts."

Ancient Romans used chopped pork, suet, egg yolks, pepper, lovage, asafoetida, ginger, rue, gravy and oil stuffed in a "paunch." American Indians have a food called "pemmican" made from dried buffalo tripe and other meats pounded with fat and stored in an animal stomach.

We suspect there is a version of haggis in every ancient culture: true nose-to-tail cuisine was the way all civilizations handled animals for food. Nothing should be wasted, so the concept is not particularly Scottish. Why the Scots continued stuffing sheep's stomachs while the rest of the world moved on to sausages using intestinal casings is one of the mysteries of history. Scots did use the intestinal casings to make black pudding, a blood sausage with oats, mealy pudding (oats, onions and suet), and bangers, breakfast sausages with a fine grind and mild spice level. But the haggis remained encased in a sheep's stomach as a traditional Scottish food.

Haggis Word Origins

And the origins of the word, haggis? The French have a word from the Middle Ages called "hachis," meaning chopped bits of animal parts. While the Scandinavian "hag," Icelandic "hoggva," and even German "hackwurst" -- meaning mixed sausage -- all could be early words for what we know today as haggis.

Vikings were known for taking their sheep with them on their marauding ventures, and they may have brought the haggis-making technique to Scotland. After all, in 1034 when King Duncan came to the throne of a united Scotland, the islands of the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland were still part of the Kingdom of Norway. The northern isles only became part of Scotland in 1468. So perhaps we have the Vikings to thank for bringing the sheep to those windswept islands, as the only meat available, and the word hag, or today haggis.

The First Haggis Recipe

The first known written recipe for haggis is from 1390, by one of the cooks for King Richard II, called Afronchemolye. The recipe calls for eggs, breadcrumbs and finely diced sheep's fat with seasoning (saffron) to be stuffed in a sheep's tripe and sewn securely, then steamed or boiled.

In 1826, "The Cook's and Housewife's Manual," produced by Meg Dods, has two recipes for haggis, including her most famous. Her haggis won what may have been an early Competition of the Haggises, held in Edinburgh, insuring her recipe would become the standard.

Hers was the haggis served at the Cleikum Club, one of the first organizations to organize Burns Nights. The Cleikum Club met at the Cleikum Inn in St. Ronans, near Pebbles and 45 miles from Edinburgh. Built in 1693, the Cleikum Inn is known today as the Cross Keys Hotel.

One of the Cleikum Club's founding members was Sir Walter Scott, and there is some speculation that Meg Dods was his mistress, and that he actually wrote her cookbook. Whatever the truth is about Sir Walter Scott and Meg Dods, haggis was well established as the Scottish National Dish by 1826 and continues to symbolize Scotland to this day.

Meg Dods may have used the sheep's stomach in 1826, but most of the haggis we sell today at Scottish Gourmet USA is made in a plastic casing, as are most on offer in Scotland from well-known maker, MacSweens.

Our ingredients are a bit simpler, too: we use only Lamb Breast, Oatmeal, Onions, Spices and 5% Beef Liver. No sheep hearts or lungs are used here in the USA. The lamb hearts are considered a delicacy and are very expensive, while use of lungs is banned in the USA.

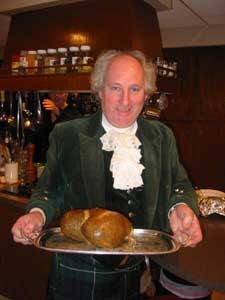

For very special events, like a Burns Supper, we do offer a Presentation Haggis, made in a natural casing (imagine a huge sausage casing). The haggis takes the shape of the casing so no two look the same.

Here's Andrew Hamilton holding one of those strangely shaped presentation haggis. You can see the twisted shape and even some of the thicker bands that reduce the height of the haggis near his right hand.

For some, Haggis is a comfort food, something that reminds them of home, and they eat it regularly. Others eat haggis only for special occasions such as Christmas, St. Andrews Night (November 30th), Hogmanay (New Years Day) and for Robert Burns Supper (around January 25th). We invite you to try our haggis, as well as some of our delicious serving tips, and start a new tradition in your family!